Journey to Palapye Road - False Dawn and New Beginnings

By Jonathan Laverick

Although van Ryneveld's team had shown it was possible to fly from London to Cape Town in March 1920, the fact that it had taken him three aircraft to do so suggested that the technology was not quite ready for widespread use. Nonetheless, the excitement generated by his flight led to a sudden rush of aviation in Bechuanaland. This would prove to be a false dawn and it was only in the second half of the decade that flying became a practical proposition in the Protectorate.

Zwartkop would become the home of the SAAF. Its original WWI hangars, donated as part of the Imperial Gift, can be seen to the left.

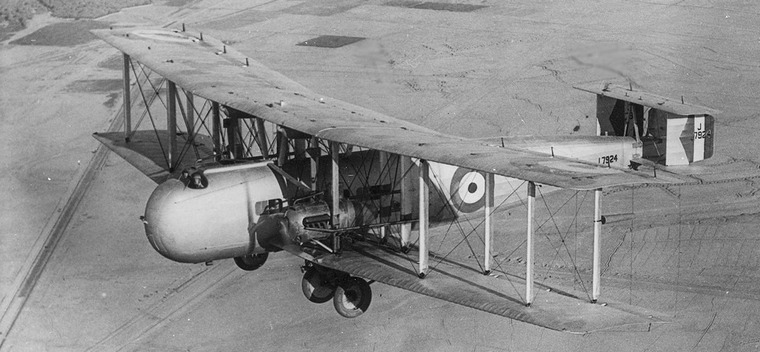

Immediately after his successful journey, Pierre van Ryneveld returned to London as Air Attaché for the Union government. He was feted for his achievements and gave many talks on the epic flight of the two Silver Queen Vimys and the DH.9, Voortrekker, which had taken him from the capital of the Empire to the southern tip of Africa. His posting, however, was a short one for in June he was recalled to Pretoria where he was appointed Director of Air Services and charged with the formation of the South African Air Force. This appointment was backdated to February 1, 1920 and this date means the SAAF has a very strong claim to be the second oldest air force in the world - even though the SAAF title was not officially used until 1923. Zwartkop became the effective home to the new service and the Imperial Gift hangars that were erected there in 1921 can still be seen there today.

Now home to the SAAF Museum, the WWI era hangars are still in use.

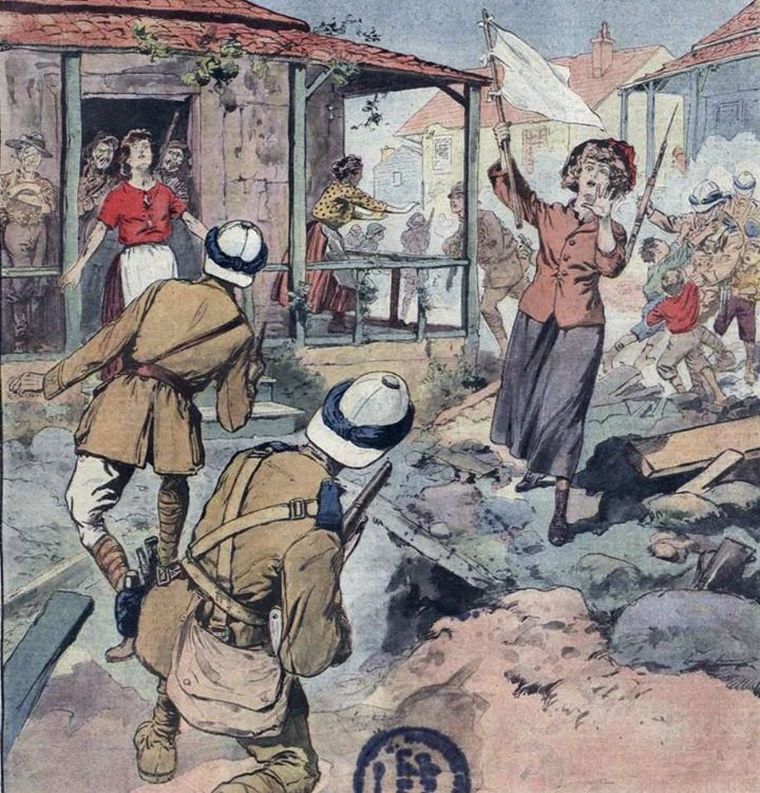

The new air force had an unusual first combat role - suppressing a strike. The Rand Rebellion was an armed uprising caused by falling wages and a prospective lowering of the colour bar to allow black miners into skilled trades (potentially lowering wages further). Despite its racist overtones, the strike was heavily supported by the Communist Party and the armed white miners took over the settlements of Benoni and Brakpan as well as the Johannesburg suburbs of Fordsburg and Jeppe. It took a military force of twenty thousand to overcome the miners in what became a heated and violent struggle. The nascent air force used several DH.9 on raids against the strikers and it is believed that Voortrekker, the aircraft that was the first to land in Bechuanaland, was lost during the brief conflict.

The Rand Revolt gained a lot of attention around the world, with communist sympathies being clear in some coverage. Le Petit Journal.

John Holthouse, the pilot who delivered the DH.9 to van Rynveld in Bulawayo via Palapye - becoming the first man to land in Bechuanaland - left the RAF for the SAAF in 1921 and eventually served as Director of Air Services before becoming the Air and Military Attaché to the USA during World War II.

The immediate aftermath of the Race to the Cape saw a new enthusiasm for flying in Bechuanaland and by the end of the year, there were four operational airfields. Palapye Road and Serowe, both built by Khama III, were joined by Artesia and Francistown. Palapye was now administered by the British and from September 1920 was effectively run by the police outpost in the settlement who then became responsible for the stock of petrol and Castrol oil that was left over from the Cape attempt.

Major Miller and one of Aerial Transport's 504K's.

Aerial Transport, an early attempt at a South African airline, requested and were granted a piece of land in Francistown for an aerodrome. This was between the River Tati and the railway line to the north west of the native location (possibly on the site of the old stadium) and the ground was cleared using prison labour for which the South African organization paid £25. While it is known that at least one of the company's Avro 504K's flew from the strip, operations came to a halt when the firm folded in November 1920.

During its thirteen-month career, Aerial Transport flew an impressive five thousand passengers. Major Allister Miller, one of the firm's founders and a pioneer of aviation in South Africa, continued flying one of the 504's in Rhodesia until it crashed two years later. This did not bring his flying career to an end as he later played a role in the creation of South African Airways.

While the world was coming to terms with aviation, the cessation of Aerial Transport's activities brought flying in Bechuanaland to a grinding stop. The administration in Mafeking received all the latest aviation laws, regulations, and maps but their required six-monthly reports on aviation in the Protectorate made for stilted reading. March to September 1921 - No Activity. September to March 1922 - No Activity. March to September 1922 - No flying here or Rhodesia. September to March 1923 - No Flying. In fact, it would be nearly five years before another record-breaking flight would relight the spark of interest in aviation in Bechuanaland.

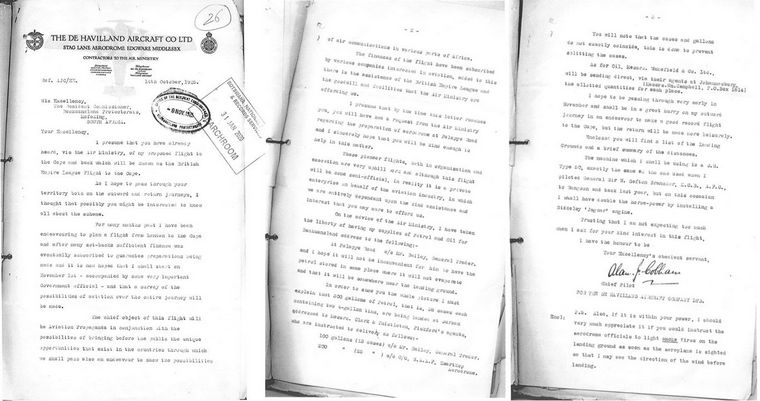

Alan Cobham's letter to the Bechuanaland authorities explaining his proposed flight and requirements. Botswana National Archives.

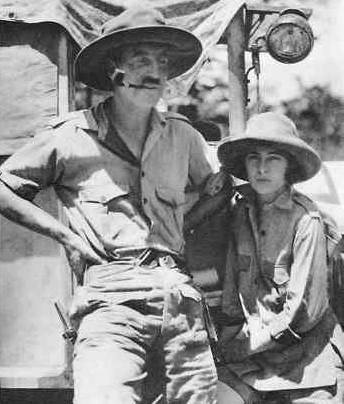

Cobham and his team. A film was made of the epic journey.

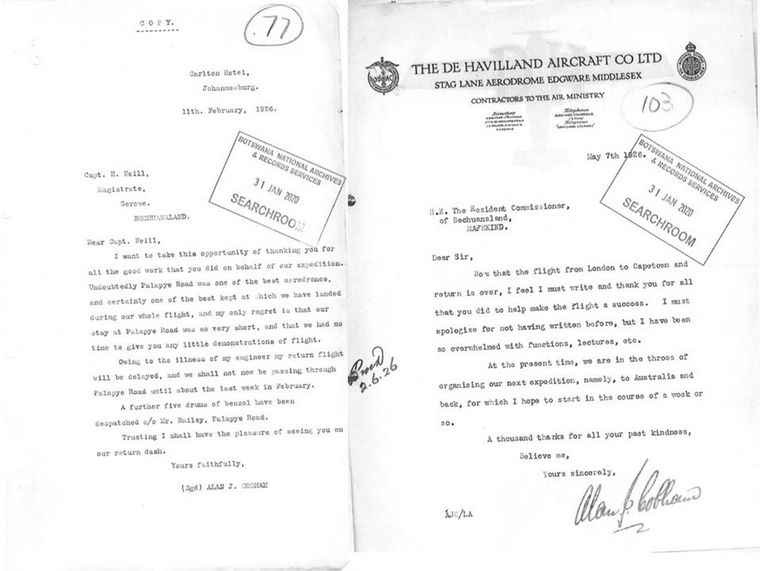

The improvements in aviation safety over the proceeding five years can be assessed through the fact that he flew his de Havilland DH.50 to Cape Town and back to London with hardly a hitch between November 1925 and March 1926. While the survey on the outward leg took ninety-four days, the return to London was made over a remarkable sixteen-day period. Cobham landed at Palapye Road on both legs of his journey and used Mr Bailey's General Store as a depot for his fuel and oil requirements, while the Palapye Hotel supplied lunches. He ranked Palapye as one of the best kept aerodromes in Africa and was profuse in his thanks to the Bechuanaland administration.

Cobham's thank you letters. Botswana National Archives.

Cobham's flight was followed by a growing stream of long distant aviators that included the Duchess of Bedford, RAF flights from Cairo and British MP's along with South African businessmen. By the beginning of 1928 local authorities were becoming concerned about the number of flights arriving in Palapye without prior notice which made refuelling a complicated business. The number of passengers flying through Palapye can be gauged by the request made in May 1928 for the airfield to be equipped with brick-built toilet facilities. The lack of available prison labour meant that they were only completed by the following March, with the funds coming out of the annual £50 maintenance grant for the airfield.

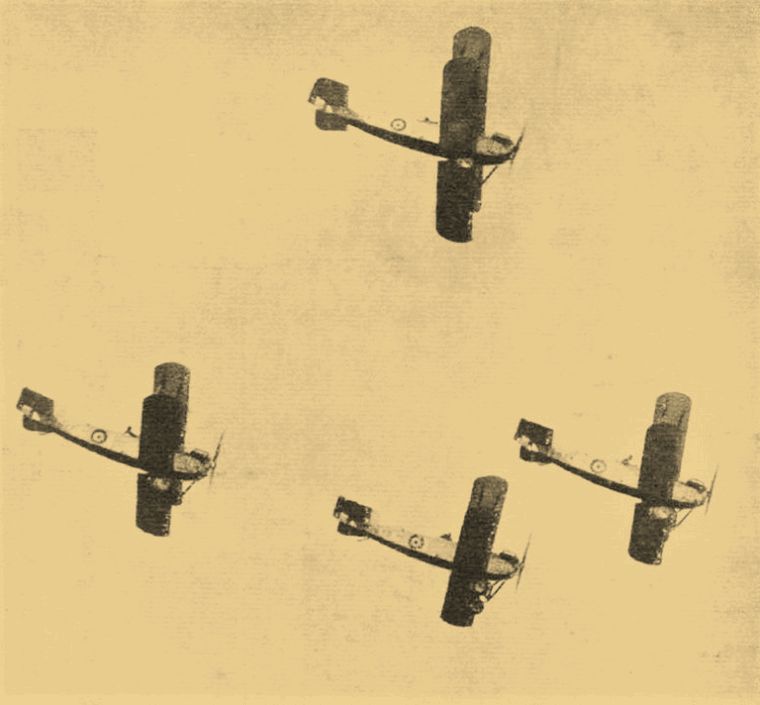

Fairy III's at the end of their Cairo to Cape flag waving flight.

Among the first visitors to make use of the lavatories was Squadron Leader Cox and his team that were flying four RAF Fairey III's from Cairo to South Africa on a flag waving exercise. This was the third Cairo to Cape RAF tour and this would become a regular fixture. The fame of the Palapye Hotel had spread far and wide and the order for refreshments was made directly from Air Vice Marshall Webb-Bowen in Cairo. He allocated four Guineas for tea and snacks that were to be brought to the airfield, stressing that the crews did not have the time for a sit-down lunch at the hotel!

These four visited Palapye on both directions of their journey.

One week in April 1929 saw a record three private flights transit Palapye, with businessmen being ferried to Salisbury and Johannesburg. Later in the year, Lieutenant Casperthus, SAAF, landed without permission en route to a hunting trip on the Zambesi. Dangers of antbear holes and livestock were highlighted by the local authorities and again there were discussions at a high level about the importance of the police in Palapye being notified of each incoming flight.

Vickers Victoria - these troop carriers became annual visitors to Palapye in the early 30's, leading to an expansion of the airfield.

Regular flights continued and Palapye continued to be the main aerodrome in Bechuanaland, although aviation in Maun was taking off. Following a visit in 1934 by four Victoria transports of the RAF's 216 squadron, based in Cairo and who had also visited during 1931, the decision was made to enlarge Palapye Road. Due to another shortage of prison labour, local workers were hired on a wage of eight pence and two pounds of mealie meal a day plus one pound of salt per month. The airfield gained an extra hundred yards to the south west, plus another hundred yards cleared of trees, but soil erosion and the river limited expansion to the west to only thirty yards. The shape of the expanded field is still clearly visible today.

AOC Dragan Rapide being filled up at Riley's garage, Maun. Photo John © Allott.

The 1930's saw an expansion of civil aviation in Bechuanaland with the Resident Commissioner, Charles Rey, giving the industry a boost - a combination of poor roads and a wife who had been a founding member of the Royal Aero Club influencing his decisions. In collaboration with the Air Operating Company of South Africa, linked to de Havilland, he established a route from Johannesburg to Maun, via Mafeking, Serowe and Rakops for passengers and mail. By 1934 this route was operated by a de Havilland Dragon Rapide. Rey worked hard to link the Protectorate with the Imperial routes to South Africa and he played a large role in bringing South African Airways to Bechuanaland. SAA started flights from Rand airport to Windhoek, via Palapye and Maun, in 1938. The aircraft used were Junker Ju-86's and the route seem to have been a success, although summer rains could be a problem with one aircraft having to be towed from the mud in Maun and another ending up on its nose in Palapye!

This Ju-86 became stuck in the mud in Maun - another ended up on its nose in Palapye under similar circumstances. John © Allott.

World War Two interrupted this development and following that conflict aircraft with longer ranges meant that Palapye lost its importance as a refuelling stop and Maun increased its pull as the center of aviation in Botswana. Francistown's base for the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association, better known as Wenela, meant that the northern city became home to one of the busiest air operations on the continent, further reducing Palapye's influence.

For a while, Francistown became one of the busiest airports in Africa with Wenela providing air transport to the South African mines. The distinctive hangar top Francistown control tower is visible.

The final nail in the coffin for Palapye Road was Gaborone being decided upon as the new capital of an independent Botswana. Flights to Palapye became less regular and few in the country are aware of its historical importance. A guest appearance in the 2016 film A United Kingdom gave a feel of what the airfield must have once been like, but unless an effort is made to save this historic airfield, then it will go the way of the other early airports. Serowe aerodrome, the first African airfield built by an African leader, is now a hospital, Artesia is a long-lost memory, Francistown was relocated long ago, Mahalapye is now an education center and RAC offices.

Amma Assante directs a United Kingdom film from under the wing of a DC-3 at Palapye airfield. The author is the 'journalist' in the hat to the left!

Palapye Road is one of the world's oldest continuously used airfields and was built by a visionary leader, Khama III. The textbooks speak of him introducing the ox-plough and it might be time to remind people that he also introduced the aeroplane to Botswana. It is now up to Batswana to save this historic site.

|

|

Copyright © 2024 Pilot's Post PTY Ltd

The information, views and opinions by the authors contributing to Pilot’s Post are not necessarily those of the editor or other writers at Pilot’s Post.

Copyright © 2024 Pilot's Post PTY Ltd

The information, views and opinions by the authors contributing to Pilot’s Post are not necessarily those of the editor or other writers at Pilot’s Post.